Imagine walking through the gates of a 10th-century trading hub like Birka or Hedeby. Among the throngs of merchants, sailors, and blacksmiths, a woman catches your eye. She doesn't wear the drab, tattered rags often depicted in gritty television dramas. Instead, she shimmers. Her shoulders are anchored by massive bronze brooches that gleam like gold. Strands of vibrant glass beads and amber swing across her chest, and as she moves, you catch the unmistakable glint of silver thread woven into the hem of her cloak.

This woman is the mistress of a prosperous household, and her attire is a masterclass in Old Norse Fashion.

For the wealthy Norse woman, clothing was never just about protection from the biting Scandinavian wind. It was a sophisticated visual language. Every pleat in her linen smock and every inch of imported silk trim shouted her family’s rank, her husband’s success in trade, and her own mastery over the domestic economy. In this exploration, we will pull back the veil on the "elite" wardrobe of the Viking Age, revealing a world of color, global trade, and intricate craftsmanship.

The Foundation of Prestige: More Than Just Wool

To understand the heights of Old Norse Fashion, we must look at the foundation. While the average farmer relied on coarse, undyed wool, the wealthy wife had access to the finest textiles the known world could offer.

The Foundation of Prestige: More Than Just Wool

The Foundation of Prestige: More Than Just Wool

Fine-Woven Wool and the Luxury of Linen

The wealthy didn't just wear wool; they wore diamond-twill wool. This was a complex weaving technique that created a subtle, shimmering geometric pattern in the fabric. It required a high-tension loom and a master weaver’s eye.

Beneath the wool, she wore a serk (shift) of bleached linen. While linen was common, the "high-fashion" version was incredibly fine, almost translucent. In some archaeological finds, such as those from the Pskov burials, we see linen shifts with hundreds of tiny, hand-pressed pleats. These pleats weren't just decorative; they were a massive display of wealth because they required three times the amount of fabric as a standard flat garment.

The Silk Road Ends in the North

Perhaps the most surprising element of Old Norse Fashion is the presence of silk. Through the "Eastern Way"—the river routes of the Volga and the Dnieper—Norse traders brought back "samite" silk from Byzantium and China.

Archaeologists have found silk in roughly 15% of the graves in Birka, Sweden. For a wealthy woman, silk was rarely used for an entire garment. Instead, it was cut into narrow strips to be used as piping or trim on the necklines and cuffs of her wool tunics. It was the "designer label" of the 10th century—a small but unmistakable sign that her family had global reach.

The Cost of Elegance: A Snapshot of Elite Textile Data

To appreciate the exclusivity of these items, we need to look at the labor and trade value involved in creating an elite Old Norse Fashion ensemble.

| Material/Item | Source | Labor/Cost Equivalent | Social Significance |

| Pleated Linen Shift | Home-grown Flax | 300+ hours of labor | High (Internal Household Status) |

| Diamond Twill Wool | Selected Sheep Fleece | 2x cost of plain wool | Peer Recognition (Quality) |

| Imported Silk Trim | Byzantium/Silk Road | Equivalent to a small cow | Global Connections (Wealth) |

| Silver/Gold Wire | Trade/Plunder | Very High | Ultimate Status (The 1%) |

| Madder/Woad Dyes | Specialized Plants | High (Requires expertise) | Visual Dominance (Power) |

Data compiled from experimental archaeology reconstructions and grave goods analysis from Birka and Oseberg.

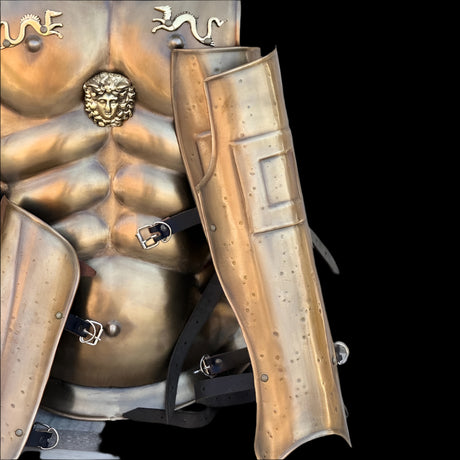

The Iconography of Power: The Oval Brooches

No discussion of Old Norse Fashion is complete without the skalspännen, or oval brooches. These were the "power suits" of the Viking woman. These large, domed bronze pins (often gilded to look like solid gold) did more than just hold up her apron dress.

A Toolbox of Precious Metal

For the wealthy wife, the brooches were anchors for her "chatelaine"—a collection of tools and charms. Hanging from her brooches on silver chains, you might find:

- A miniature silver spoon (for ear cleaning or cosmetic use).

- A set of bronze tweezers.

- An intricately carved bone needle case.

- The keys to the household chests.

The keys were the ultimate status symbol. In a culture where the "house-mistress" (húsfreyja) held total authority over the farm’s resources while the men were away, the jingle of keys against her Old Norse Fashion attire was a reminder of her legal and social power.

Silver Threads and Golden Braids

One of the most unique aspects of elite Old Norse Fashion was the use of "tablet weaving" with precious metals. This wasn't just embroidery; it was the process of weaving silver or gold wire directly into the fabric bands that trimmed a cloak or tunic.

The Oseberg Queen’s Legacy

The Oseberg ship burial in Norway, dated to 834 AD, provided a treasure trove of these textiles. One of the women buried there—likely a queen or high priestess—was found with remnants of tablet-woven bands featuring complex patterns made of real silk and silver.

These bands were so narrow and intricate that they could only be produced by someone with incredible dexterity and hours of free time. For the wealthy wife, wearing these meant she had the "staff" to produce such beauty, or the silver to buy it from a specialist.

The Colors of the High-Born

In the United States, we often imagine the Vikings in shades of mud and grey. The reality of Old Norse Fashion was a riot of saturated color. However, color was strictly tiered by wealth.

The Expensive Blues and Reds

- Woad Blue: Achieving a deep, dark blue required multiple "dips" in a fermenting woad vat. This was time-consuming and expensive. A dark blue wool dress was a clear indicator of high social standing.

- Kermes Red: While "madder" provided a common orange-red, the elite used "kermes"—a dye made from the eggs of Mediterranean insects. This produced a brilliant, crimson red that was purely a luxury import.

When a wealthy woman entered a longhouse, the vibrancy of her Old Norse Fashion garments would literally glow in the firelight, setting her apart from the thralls and free farmers in their undyed, brownish-grey wools.

Challenging the "Uniform": Was it Always the Apron Dress?

A common counterargument in the study of Old Norse Fashion is that the "apron dress" (smokkr) was the universal uniform for all women. However, recent research suggests that elite women may have opted for different silhouettes as they aged or gained status.

Challenging the "Uniform": Was it Always the Apron Dress?

Challenging the "Uniform": Was it Always the Apron Dress?

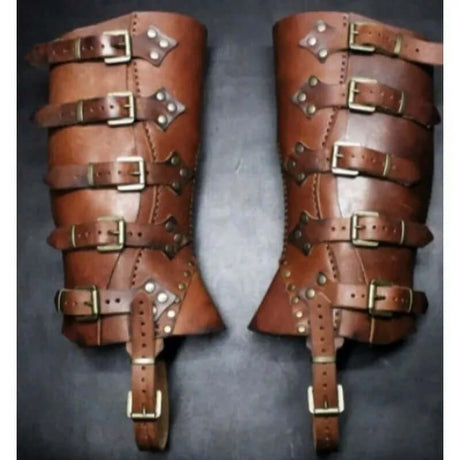

The Kaftan Influence

In Eastern Viking territories, such as modern-day Russia and Ukraine, wealthy Norse women began adopting the kaftan—a long, front-opening coat inspired by Steppe nomads and Byzantine officials. These kaftans were often held closed by beautiful "trefoil" or "equal-armed" brooches instead of the traditional oval ones.

This suggests that Old Norse Fashion was not a static, "traditional" costume but a living, breathing trend-cycle that responded to international influences. The wealthy wife was the first to adopt these "foreign" styles, using them to show how far her family’s influence extended.

The Practicality of Glamour

It is easy to assume that these elaborate outfits were purely for show, but the wealthy Norse woman was still an active participant in her world. Her Old Norse Fashion had to be functional.

The wool, no matter how finely woven, was still water-resistant due to the natural lanolin. The silk trims were durable. Even the heavy brooches served to keep her layers secure while she moved between the dairy, the loom, and the feast hall. It was a "luxury of utility"—clothing that could withstand a voyage across the Baltic but still look magnificent at a king's banquet.

The Spiritual Dimension of Dress

For the Norse, clothing also had a protective, almost magical quality. We see this in the "Position of the Brooches." Wealthy women were often buried with their brooches in very specific alignments, perhaps to protect the soul or identify their status in the afterlife.

The silver threads and geometric patterns weren't just "pretty"; they were often based on traditional knotwork meant to ward off ill fortune. To wear elite Old Norse Fashion was to wrap yourself in a protective layer of ancestral tradition and modern success.

-

You may also want to check out this product: Retro Ruffles Corset Layered Dress

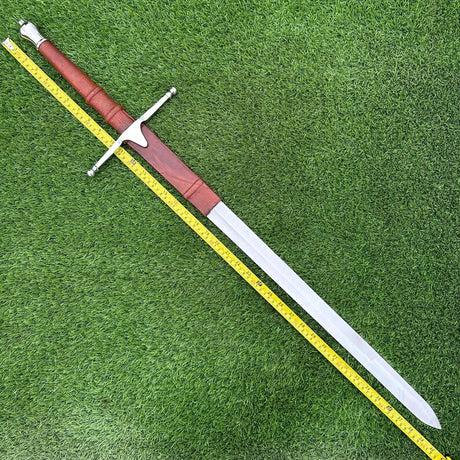

Recreating the Look: A Guide for Modern Enthusiasts

If you are an enthusiast in the United States looking to recreate an elite Old Norse Fashion look for a festival or reenactment, here is how to achieve that "Wealthy Wife" status:

- Prioritize the Fabric: Skip the "craft store" felt. Look for 100% wool in a diamond or herringbone twill. The texture is what gives the outfit its soul.

- Invest in the Hardware: Your oval brooches are your centerpiece. Look for cast bronze replicas with high detail. If they look like "costume jewelry," the whole effect is lost.

- The "Hidden" Silk: You don't need a silk dress. Add 1-inch strips of silk habotai or samite to the neckline of your wool tunic. It is a subtle, historically accurate nod to wealth.

- The Bead Count: Don't just string random beads. Look for replicas of "tortoise-shell" glass or amber. A wealthy wife would have dozens of beads, not just a few.

Conclusion

The wealthy wife’s wardrobe was the pinnacle of Old Norse Fashion. It was a bridge between the rugged reality of the North and the sophisticated luxury of the East, weaving together the living Tales of Valhalla with the practicalities of the physical world. It showed a woman who was a manager, a traveler, a weaver, and a queen of her domain.

When we look at these silks, silver threads, and bronze brooches, we see a culture that refused to be limited by its geography. The Vikings may have lived at the edge of the world, but through their fashion, they brought the whole world to their doorstep.

Old Norse Fashion tells a story of a people who were just as concerned with beauty and status as they were with battle and ships. It is a story of threads that have not yet broken, even after a thousand years.

"Tales of Valhalla is an expert chronicler of the Viking Age, blending scholarly research with master storytelling to revive the Old North. From the hidden depths of Norse mythology to the tactical grit of the sagas, they provide authentic, rich insights into the warriors, leaders, and legends that forged history." - Specialist in Norse mythology and Viking history