When we picture the Vikings, our minds often drift west—to the raids on England, the settlement of Iceland, and the legendary voyages to North America. But this is only half of their incredible story. While the Danes and Norwegians looked to the stormy North Atlantic, another group of Norsemen, primarily from what is now Sweden, turned their dragon-prowed ships eastward, navigating a vast and treacherous network of rivers deep into the heart of Eastern Europe. They were known as the Varangians, or the Rus', and their journey would lead to the very foundation of the first East Slavic state. This raises a fascinating and often controversial question: Does Russia have Swedish Viking roots?

The answer is a complex and compelling "yes," but not in the way you might think. This isn't a story of a massive Viking invasion that replaced a local population. Instead, it’s a tale of a skilled and ambitious Norse elite who, through trade, mercenary work, and political savvy, established themselves as rulers over a vast Slavic territory. Unraveling the evidence for Russia’s Swedish Viking roots takes us through ancient chronicles, remarkable archaeological sites, and a historical debate that continues to this day.

The Eastern Call: Why Swedish Vikings Looked to the Rivers

While their Norse brethren were terrorizing the coasts of Western Europe, the Swedish Vikings were drawn by a different, though equally powerful, allure: the immense wealth of the East.

The Eastern Call: Why Swedish Vikings Looked to the Rivers

The Lure of Silver and Silk: The Great Eastern Markets

The ultimate prizes lay far to the southeast: the Byzantine Empire, which the Norse called Miklagard ("The Great City," Constantinople), and the rich Abbasid Caliphate in the Middle East, known as Serkland ("Land of the Saracens"). These civilizations were sources of unimaginable wealth for the Scandinavians.

- Silver Dirhams: Arab silver coins, known as dirhams, flowed north in vast quantities, traded for the goods the Vikings could provide. Thousands of these coins have been found in Viking hoards in Sweden, a testament to the scale of this trade.

- Luxury Goods: Silk, spices, glass beads, wine, and fine jewelry were other coveted items that the Vikings sought from these powerful southern empires.

The River Highways: The Path to Riches

Unlike the open seas of the Atlantic, the path to the East was a network of interconnected rivers. The Swedish Vikings, with their versatile longships that had a shallow draft, were uniquely equipped to navigate these waterways. The two main routes were:

- The Volga Trade Route: This route went from the Baltic Sea, up rivers like the Neva, across lakes, and down the mighty Volga River to the Caspian Sea, giving access to Central Asia and the markets of the Caliphate.

- The Dnieper Trade Route (the "Route from the Varangians to the Greeks"): This path led down the Dnieper River to the Black Sea and the ultimate prize: the golden city of Constantinople.

These rivers were the highways of the Viking Age in the East, and controlling them was the key to immense wealth and power. This context is crucial for understanding the origins of Russia's Swedish Viking roots.

Story Vignette 1: Kettil's Choice Kettil, a young man from a farm near Lake Mälaren in Sweden, was tired of the poor soil and the endless toil. Every year, he saw men return from the East, their pouches heavy with strange silver coins and their stories full of sprawling cities and perilous rivers. They spoke not of raiding monasteries, but of trading fine furs for silk and silver. Kettil looked at his calloused hands, then at the axe leaning against the wall—an axe for chopping wood, not for glory. He made a decision. He would join a crew heading east. He would become a Varangian. He would row the great rivers and see Miklagard for himself. He was unknowingly about to become part of the story of Russia's Swedish Viking roots.

The Primary Chronicle and the "Invitation" of the Rus'

Our main literary source for the founding of the first East Slavic state comes from the Russian Primary Chronicle (also known as The Tale of Bygone Years), a history compiled in Kiev around 1113 AD. It tells a remarkable story.

The Tale of Rurik: A Call for Order

According to the chronicle, by the mid-9th century, the local Slavic and Finnic tribes had driven out the Varangians to whom they had been paying tribute. However, they soon fell into chaos and internal conflict.

- The Invitation: The chronicle states that in the year 862 AD, the tribes decided to seek a prince from overseas to rule them and bring order. A delegation was sent across the sea to the Varangian Rus', with the famous message: "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us."

- Rurik and his Brothers: Three brothers—Rurik, Sineus, and Truvor—answered the call. Rurik established himself in Novgorod, while his brothers took other towns. After his brothers' deaths, Rurik consolidated his rule.

- Establishing a Dynasty: Rurik's successor, Oleg (Old Norse: Helgi), captured the strategic city of Kiev further south, moving the capital there and creating the state that would become known as the Kievan Rus'. The dynasty founded by Rurik would rule for over 700 years. This chronicle is the foundational text supporting the theory of Russia's Swedish Viking roots.

The Normanist Debate: A Fierce Historical Controversy

The story from the Primary Chronicle forms the basis of what is known as the "Normanist Theory" of the origin of Russia. However, this theory has been the subject of intense debate for centuries.

The Normanist Theory

This is the mainstream view held by the vast majority of Western and many modern Russian historians. It posits that the "Rus'" were indeed Scandinavians (primarily Swedes) and that this Norse elite played a foundational role in organizing the first East Slavic state. This theory is supported by a wealth of evidence beyond the chronicle itself, confirming significant Swedish Viking roots.

The Anti-Normanist Theory

This counter-argument, which gained particular prominence for nationalist reasons during the Soviet era, claims that the Rus' were a Slavic tribe from the south. Proponents of this view argue that the Primary Chronicle is unreliable, a later invention designed to legitimize the Rurikid dynasty with a prestigious foreign origin. They downplay the evidence of Swedish Viking roots and emphasize the Slavic foundations of the state.

Weighing the Evidence

While it's true that the Primary Chronicle was written centuries after the events it describes and contains legendary elements, the overwhelming archaeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence strongly supports the Normanist view. The evidence for Swedish Viking roots in the formation of the Kievan Rus' is substantial.

Unearthing the Truth: The Archaeological and Linguistic Evidence

Beyond the chronicle, tangible evidence paints a clear picture of a significant Norse presence in early Russia.

Scandinavian Graves and Artifacts

Archaeological excavations at key sites along the river routes have uncovered a treasure trove of distinctly Scandinavian artifacts.

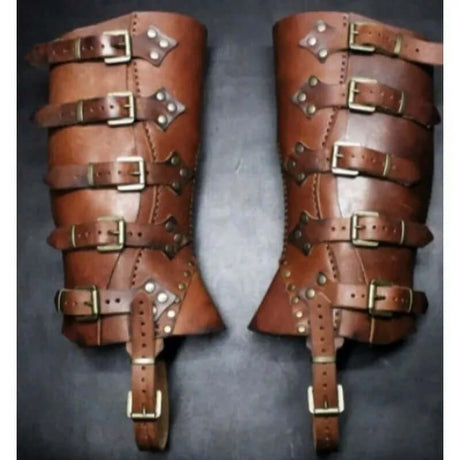

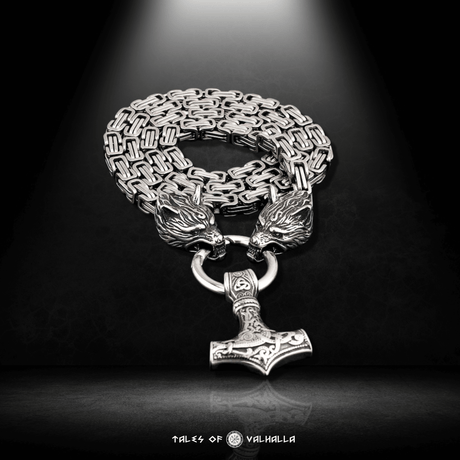

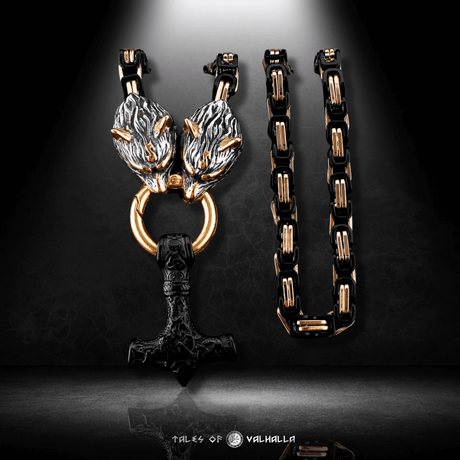

- Staraya Ladoga: Often considered the first "capital" of the Rus', this site contains Scandinavian-style burials, brooches, amulets of Thor's hammer, and other artifacts dating back to the 8th century.

- Gnezdovo: A massive 10th-century settlement near modern Smolensk, it contains hundreds of burial mounds, many of which are classic Scandinavian boat burials, containing Viking weapons, jewelry, and tools.

- The Finds: The types of artifacts found—oval brooches worn by Scandinavian women, swords with characteristic hilts, Thor's hammer pendants—are identical to those found in Sweden from the same period. This physical evidence is perhaps the strongest proof of Russia's Swedish Viking roots.

The Linguistic Trail: Names and Words

Language provides another powerful line of evidence.

- The Name "Rus'": The most widely accepted theory is that the name "Rus'" derives from the Old Norse term roðsmenn or roðskarlar, meaning "the men who row." This would be a fitting name for people who navigated the vast river systems. The Finnish name for Sweden, Ruotsi, is derived from the same root.

- Norse Names: The names of the first Rus' rulers mentioned in the chronicle are clearly Norse in origin: Rurik (from Old Norse Hrærekr), Oleg (Helgi), Igor (Ingvarr), and Olga (Helga).

- The Dnieper Rapids: The Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, writing in the 10th century, listed the names of the Dnieper rapids in both Slavic and "Rhos" (Rus'). The "Rhos" names he listed are clearly Old Norse. This is a crucial contemporary source confirming the Norse language of the Rus' elite.

Genetic Clues

Modern DNA studies have also contributed to the discussion. Genetic analysis of remains from Rus' burial sites and of modern populations in the region has shown clear Scandinavian genetic markers, further supporting the narrative of Swedish Viking roots.

Table: Summary of Evidence for Swedish Viking Roots in Russia

This table summarizes the diverse and compelling body of evidence that underpins the theory of Russia's Swedish Viking roots.

From Varangian to Slav: The Process of Assimilation

It is crucial to emphasize that the Norse Rus' were a small ruling minority. They did not replace the existing Slavic population but rather ruled over them. Over time, this Norse elite gradually assimilated into the dominant local culture.

From Varangian to Slav: The Process of Assimilation

- Adopting Slavic Language and Customs: Within a few generations, the Rus' rulers began adopting Slavic names, language, and customs. For example, Rurik's great-grandson, Sviatoslav, had a Slavic name, although he was noted for his Norse appearance and customs. His own son, Vladimir, had a Slavic name.

- The Conversion of Vladimir the Great: The pivotal moment of assimilation came in 988 AD when Vladimir the Great, the ruler of Kievan Rus', officially adopted Orthodox Christianity from the Byzantine Empire. This act decisively aligned the Kievan Rus' with the Byzantine and Slavic Christian world, cutting it off culturally and religiously from its pagan Scandinavian origins. This marked a significant turning point in the story of Russia's Swedish Viking roots.

The Varangian Guard: Vikings in the Service of the Emperor

The connection between Scandinavia and the East wasn't limited to the Kievan Rus'. Many Norsemen, after traveling the river routes, continued on to Constantinople to serve as elite mercenaries in the Byzantine Emperor's personal bodyguard: the legendary Varangian Guard.

- Elite Mercenaries: The Varangian Guard was famous throughout the medieval world for its fierce loyalty (to the Emperor who paid them, at least), incredible strength, and battle prowess. They were the emperor's shock troops and last line of defense.

- A Path to Wealth and Fame: Serving in the guard was an extremely prestigious and lucrative career. Many Scandinavians joined the guard, amassed a fortune in gold, and then returned home as wealthy and respected men.

- Harald Hardrada's Story: The most famous example is Harald Hardrada. After being exiled from Norway, he traveled to Kievan Rus' and then to Constantinople, where he became a high-ranking commander in the Varangian Guard. He fought in campaigns across the Mediterranean, became fabulously wealthy, and eventually returned to Norway to claim the throne. His story exemplifies the path of the Varangian adventurer.

Story Vignette 2: The Guard's Vigil Sven stood sentinel in the opulent Blachernae Palace in Constantinople, the air heavy with incense and the murmur of Greek courtiers. His hand rested on the hilt of his axe. He and his fellow Varangians, all tall Northmen, stood like statues of iron amidst the silk and marble. They were far from the fjords of home, but here in Miklagard, they were feared and respected. They were the Emperor's Guard. Their loyalty was to the gold he paid them and to each other. They were a brotherhood of exiles and adventurers, the final destination for many who followed the eastern river roads, a living testament to the far-reaching legacy of their Swedish Viking roots.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Rus'

So, does Russia have Swedish Viking roots? The answer, supported by a wealth of evidence, is a definitive yes. The foundational state of Kievan Rus', the precursor to modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, was established and ruled by a Norse elite, known as the Rus' or Varangians, who originated primarily from Sweden.

However, this is not a story of conquest and replacement. It is a story of a small, dynamic group of traders and warriors who integrated themselves into a vast Slavic land, serving first as mercenaries, then as rulers. Over time, they assimilated, adopting the local language, religion, and culture, so that within a few centuries, their Scandinavian origins became a distant memory. The legacy of their Swedish Viking roots is not one of overt, lasting Scandinavian culture, but of the political and social structures they helped to create, and even in the very name of the nations that grew from their domain. The tale of the Rus' is a powerful reminder of the Vikings' incredible reach and their profound, and often surprising, impact on the course of world history.

4 FAQs

-

Q: So, does Russia really have Swedish Viking roots? A: Yes, the foundational state of the Eastern Slavs, known as the Kievan Rus' (from which modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus descend), was established and ruled by a Norse elite called the Rus' or Varangians. Overwhelming evidence shows these Rus' originated primarily from what is now Sweden. So, while it wasn't a mass migration, the first ruling dynasty had clear Swedish Viking roots.

-

Q: Who were the "Rus'" or "Varangians" mentioned in early Russian history? A: The "Rus'" or "Varangians" were Scandinavian Vikings, mostly from Sweden, who chose to travel east instead of west. They were renowned as traders and mercenaries who expertly navigated the river systems of Eastern Europe, connecting the Baltic Sea to the immensely wealthy Byzantine Empire and the Arab Caliphates.

-

Q: How did these Swedish Vikings come to rule over the Slavic tribes? A: According to the Russian Primary Chronicle, the local Slavic and Finnic tribes were suffering from internal conflict and were unable to govern themselves. Around 862 AD, they reportedly sent a delegation overseas to the Rus' with an invitation: "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us." The Rus' chieftain Rurik accepted, establishing a dynasty that would rule for centuries.

-

Q: If Vikings ruled early Russia, why don't Russians speak a Scandinavian language today? A: The Norse Rus' were a very small ruling minority governing a vast Slavic-speaking population. Over the course of a few generations, they completely assimilated. They adopted Slavic names, the local Slavic language, and in 988 AD, Orthodox Christianity. This religious and cultural shift aligned them fully with the Slavic and Byzantine world, effectively severing the ties to their Swedish Viking roots.