When the word "Viking" comes to mind, most of us in the United States immediately picture foggy shorelines, the white cliffs of England, and the vast, icy expanse of the North Atlantic. The standard narrative confines them to raiding monasteries like Lindisfarne or settling in places like Normandy, Ireland, and Vinland.

But what if I told you that the legendary longships, those "dragons of the sea," sailed so far south that the Northmen traded snow and ice for sand and searing heat? That they clashed not with Saxon kings or Celtic chiefs, but with Berbers, Arabs, and the naval forces of an Islamic caliphate?

This is the dramatic, little-known truth of The Viking Raid in Africa.

My own journey into this history began with a simple map, tracing the immense reach of the Viking world. Seeing a thin, dotted line extend past the Pillars of Hercules and down the African coast was a moment of genuine awe. It reshaped my understanding of these people from mere regional raiders to global, opportunistic explorers whose ambition was as boundless as the ocean.

In this comprehensive 2,500-word exploration, we will sail with these forgotten raiders. We will analyze the historical context, dissect the primary sources, identify the specific targets of The Viking Raid in Africa, and understand the profound geopolitical ripple effects of this astounding journey. Prepare to dismantle the myths and discover a truly global Viking Age.

The Voyage to the Sun: Setting the Stage for The Viking Raid in Africa

The most significant and well-documented instance of The Viking Raid in Africa occurred between 859 and 862 CE. This wasn't a minor skirmish; it was a grand expedition, a three-year odyssey led by two of the most legendary figures of the late Viking Age.

The Voyage to the Sun: Setting the Stage for The Viking Raid in Africa

Björn Ironside and Hastein: The Leadership Duo

This ambitious fleet was spearheaded by Björn Ironside, a figure often identified in sagas as the son of Ragnar Lothbrok, and his mentor, Hastein (Hasting). While the truth behind their parentage is debated, their ambition was not. They had already spent years raiding the Frankish kingdoms, accumulating immense wealth and experience.

Their strategy was simple: the familiar coasts of Europe were becoming too well-defended. They needed new, untapped sources of wealth, and that meant pushing the boundaries of the known world. The Mediterranean—the "Middle Earth" of the classical world—beckoned, and beyond it, the wealthy shores of North Africa.

The Long Journey South

The journey itself was a feat of navigational prowess. They sailed from the Bay of Biscay, rounding the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal). This put them in direct confrontation with the mighty Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba, the Islamic power that controlled Al-Andalus.

- Crossing the Strait: They successfully passed through the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, known to the ancients as the Pillars of Hercules, a monumental symbolic and logistical achievement.

- Geopolitical Shift: This act instantly transformed them from raiders of Christian Europe to raiders operating in the complex, highly militarized world of the Islamic Mediterranean. The Viking Raid in Africa officially began as soon as they entered this new theatre.

Expert Insight: Professor Simon Coupland, a key scholar on this era, notes: "The 859-862 CE expedition was a 'grand tour' of plunder. It demonstrates that the Vikings' defining trait was not merely aggression, but an audacious geographical curiosity and a ruthless pragmatism for finding weaknesses in distant, wealthy targets."

🎯 The Targets: Unveiling the Sites of The Viking Raid in Africa

The focus of the operation wasn't just Africa in a general sense; the Vikings had specific, wealthy coastal targets in the region then known as the Maghreb.

North Morocco: The Initial Landing

The first recorded strike by the fleet after passing Gibraltar was along the coast of Morocco. Historical Arabic chronicles, which are primary sources for The Viking Raid in Africa, detail attacks on the kingdom of Nekor (present-day Al-Rif).

- The Capture of Nekor: In 859 CE, the Vikings launched an assault, seizing the town. The Arabic chronicler, Al-Bakri, records that the town's population was forced to flee.

- Primary Objective: While the coastal town itself provided some plunder, the main prize was often the capture of slaves for ransom and sale, a crucial element of the Viking economy.

Raiding the Hafs al-Kabir

Following the Moroccan coastal assaults, the fleet continued eastward into the Western Mediterranean. The next crucial phase of The Viking Raid in Africa brought them to the Balearic Islands and later, potentially, as far as the mouth of the Nile or the Tunisian coast.

| North African Raiding Target | Date (Approx.) | Contemporary Region | Recorded Impact |

| Nekor | 859 CE | Northern Morocco | Sacked, inhabitants fled; ransom taken. |

| Balearic Islands | 860 CE | Western Mediterranean | Severe damage, indicating successful raids. |

| Algerian Coast | 860 CE | Algeria/Tunisia | Skirmishes with local naval forces. |

| Further Eastward | Unconfirmed | Eastern Mediterranean | Indications they sought the Nile but turned back due to naval opposition. |

The ability of the Vikings to sustain a multi-year expedition hundreds of miles from their home base, crossing cultural and military boundaries, is a staggering logistical achievement that underscores the gravity of The Viking Raid in Africa.

The Clash of Civilizations: Vikings vs. The Islamic World

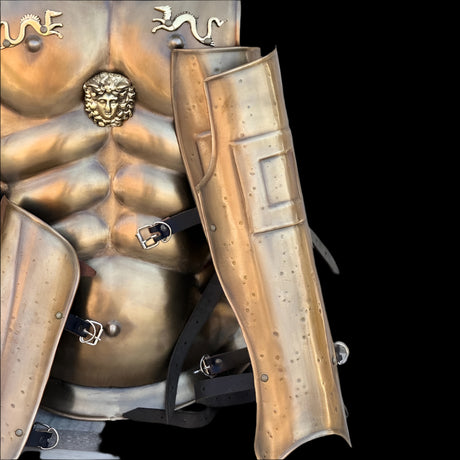

This expedition was unique because it pitched the pagan, Northern European fighting style against the sophisticated, highly organized military forces of the medieval Islamic world. This was a true clash of civilizations, and the records offer a rare comparative glimpse into two powerful cultures.

The Naval Opposition

The Vikings were masters of the longship—fast, shallow-draft vessels perfect for hit-and-run raids. However, the naval forces of the Islamic caliphates in Al-Andalus and North Africa were highly developed, relying on heavier, oar-powered galleys.

- Counter-Action: Spanish Arabic sources record that the Emirate of Córdoba quickly mobilized their fleet, known as the thalassa, to pursue and neutralize the threat. They had already dealt with earlier, smaller Viking incursions in the 840s, so they were prepared.

-

The Outcome: The Viking Raid in Africa ultimately stalled in the Eastern Mediterranean. They faced fierce and coordinated resistance, confirming that while the Vikings were adaptable, they were not invincible against organized naval power. The logistical challenge of sustaining a long war far from home also played a pivotal role in their decision to turn back.

Real-Life Example: The Return Journey

On their return trip through the Strait of Gibraltar, the Umayyad fleet ambushed them, inflicting crippling losses. According to chroniclers, they lost up to 40 ships in a single battle. This forced engagement illustrates that The Viking Raid in Africa was not a one-sided affair; the local powers retaliated decisively. The Vikings, accustomed to overwhelming local forces, met their match.

See more: Whispers of the North: Unlocking the Secrets of The Elder Futhark Runes

Analyzing the Economics and Logistics of The Viking Raid in Africa

The sheer scale of this three-year voyage allows us to analyze the economic and logistical drivers of high-level Viking long-distance raiding.

Analyzing the Economics and Logistics of The Viking Raid in Africa

The Economics of Plunder and Trade

The main economic motive behind The Viking Raid in Africa was the acquisition of silver (the primary currency of the Viking world) and slaves.

- Silver Sources: Raiding the wealthy cities and markets provided vast quantities of silver dirhams and gold dinars from the Islamic world.

- The Slave Trade: Slaves, captured in both Christian and Muslim lands, were highly profitable commodities. They could be sold in the thriving slave markets of the Mediterranean or transported back north.

The successful navigation and sustenance of 62 ships (the estimated size of the fleet) for three years highlights an exceptional level of organization, leadership, and resource management. This was an enterprise akin to a modern corporate merger, with extremely high risk and potential return.

The Statistical Overview of the Grand Tour

| Viking Expedition | Primary Leaders | Duration (Years) | Estimated Fleet Size (Peak) | Success Metric |

| Great Heathen Army (England) | Ivar the Boneless, etc. | 14+ | 200+ Ships | Permanent Settlement/Conquest |

| Frankish Raids (Seine) | Various | Ongoing | 100+ Ships | Ransom (Danegeld) |

| The Viking Raid in Africa (859-862) | Björn Ironside, Hastein | 3 | 62 Ships | Plunder and Geographic Exploration |

While the African raid didn't result in conquest like the Great Heathen Army, it was arguably the most ambitious journey of pure exploration and opportunistic plunder of the Viking Age. It expanded the Viking brand across half the world.

Counterarguments and Alternative Perspectives

When discussing an event as dramatic as The Viking Raid in Africa, we must consider the nuances and alternative interpretations, particularly given the reliance on non-Norse, often hostile, source material.

The Chronicler Bias

Our primary records come from Frankish and, more importantly, Arabic chroniclers. These were often writers who viewed the Vikings as destructive, godless pagans.

- Exaggeration of Damage: It is likely that the extent of the damage and the size of the Viking forces were exaggerated to emphasize the chroniclers' own powerlessness or to glorify the counter-efforts of their local rulers.

- The "Lump" Raider Problem: The term "Viking" often became a catch-all for any sea-raider operating outside the law. Some of the later, less-substantiated raids attributed to "Vikings" in the Mediterranean might have been carried out by Norse mercenaries or other local pirate groups.

The "Trade First, Raid Second" Theory

Some modern historians argue that the grand tour was not purely a raid. It was an expedition to find and establish new, profitable trade routes to access the gold, spices, and ivory of the South. The Viking Raid in Africa may have been the violent means to an economic end, establishing trade relationships through force that would later facilitate peaceful exchange.

Challenge to the Conclusion: Could the "failure" to establish a permanent presence in Africa actually be a sign that trade was the intended goal, and the raids were simply a way to clear the path? The fact that the Vikings established permanent, thriving trade posts in Russia, which also required long-distance sailing, supports this possibility.

The Legacy: How The Viking Raid in Africa Reshaped the Viking World

The 859-862 CE expedition, though geographically distant, profoundly impacted the trajectory of the Viking Age.

Changing the Game of Raiding

The sheer distance covered proved that no coastline was safe. This set a new standard for Viking ambition, influencing later generations of explorers and raiders who pushed further west to Iceland and Greenland. The Viking Raid in Africa served as a blueprint for long-distance logistics.

Cultural Exchange and the "Black Northmen"

While the raid was primarily destructive, it fostered involuntary cultural exchange. Slaves taken from North Africa back to Scandinavia and Norse colonies introduced new genes, goods, and potentially new technologies and ideas to the North.

Furthermore, the Arabic descriptions of these Norsemen are fascinating, calling them Majus (fire-worshippers) or describing their hygiene, hair color, and dress. This cross-cultural description is a historical treasure, giving us an external mirror on the Vikings. The memory of The Viking Raid in Africa was preserved in a vibrant non-European context, making it a unique element of the global history of the Viking Age.

Conclusion: A Saga Written in Sand

The Viking Raid in Africa is a thrilling, essential chapter in Viking history, a testament to the audacious spirit of exploration and plunder that defined the era. It shatters the myth of the Vikings as isolated Northmen, revealing them instead as true global players whose longships were as comfortable in the warm, indigo waters of the Mediterranean as they were in the cold, gray swells of the Irish Sea.

The journey of Björn Ironside and Hastein reminds us that the Viking Age was not a simple regional history; it was a period of intense global interconnectivity. The echoes of their longships can be found not just in the ruins of English monasteries, but in the detailed chronicles of Islamic historians. Their failure to settle the region is just as important as their success in reaching it, demonstrating the strength of the African and Islamic powers they encountered.

For the modern American audience, The Viking Raid in Africa provides a powerful lesson: never underestimate the ambition of a motivated explorer, and never accept a history that limits their scope. The Vikings sought wealth, power, and glory, and they were willing to sail to the very ends of the Earth—or at least, to the shores of North Africa—to find it.