When you hear the phrase "Westward Expansion," your mind likely drifts to images of covered wagons rattling across the American Great Plains, cowboys herding cattle in Texas, or prospectors panning for gold in California. It is the quintessential American story of "Manifest Destiny"—the drive to push the frontier ever closer to the setting sun.

But a thousand years before Lewis and Clark dipped their paddles into the Missouri River, a different kind of pioneer was undertaking a Westward Expansion of their own.

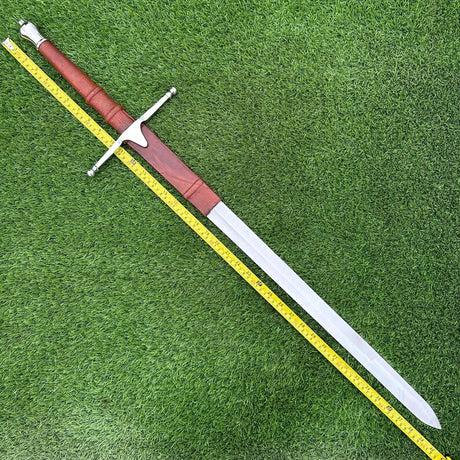

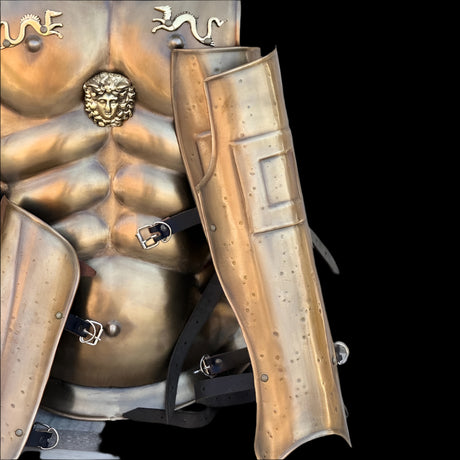

They didn't have wagons; they had longships. They didn't have rifles; they had bearded axes. And they weren't crossing a prairie of grass; they were crossing a prairie of cold, grey Atlantic ocean.

This is the story of the Viking Age Westward Expansion. It is a saga of outlaws, explorers, and farmers who pushed the boundaries of the known world from Norway to the strange, grape-filled shores of North America. Today, we are going to trace their wake, separate the myths from the maps, and understand how this incredible movement of people set the stage for the modern world.

The Spark: What Fueled the Viking Westward Expansion?

Why leave?

That is the fundamental question of all migration. Why would a farmer in a fjord in Norway pack his entire family, his cattle, and his belongings into an open boat and sail into a terrifying void?

The Viking Westward Expansion wasn't driven by a single factor. It was a perfect storm of political pressure, population growth, and pure, unadulterated opportunity.

The Spark: What Fueled the Viking Westward Expansion?

The Push: Politics and Overpopulation

In the late 8th and early 9th centuries, Scandinavia was changing. Powerful kings, most notably Harald Fairhair of Norway, were consolidating power. They were taxing independent chieftains and demanding submission.

For many proud Norsemen, bowing to a king was unacceptable. The choice was simple: Submit, or leave.

Simultaneously, the population was booming. The steep, rocky fjords of Norway offered limited arable land. If you were a second or third son, you had no inheritance and no farm. The only way to get land was to find it. This hunger for soil was the engine of the Westward Expansion.

The Pull: Free Land and Freedom

To the West lay islands. First the Shetlands and Orkneys, then the Faroes. These were stepping stones. They offered grazing land for sheep and safe harbors for ships.

But the rumors of what lay further west—massive islands with no kings and free land—were the ultimate lure. The Viking Westward Expansion was, at its heart, a quest for autonomy.

Phase One: Iceland – The Republic of Fire and Ice

If the Westward Expansion had a "wild west" boomtown, it was Iceland.

Discovered (accidentally) by Naddodd the Viking and later circumnavigated by Gardar Svavarsson, Iceland was the first major leap into the open ocean. Settled definitively around 874 AD by Ingólfr Arnarson, Iceland represented the dream of the Westward Expansion.

A Land of Law and Lava

Iceland was unique. It had no king. Instead, the settlers established the Althing in 930 AD—one of the world's first parliamentary institutions.

The migration was massive. In a span of just sixty years (the "Settlement Age"), thousands of Norsemen poured into Iceland. They brought with them a spirit of independence that defined the Westward Expansion. They weren't just exploring; they were building a new society from scratch on the edge of the inhabitable world.

Expert Insight:

"The settlement of Iceland is one of the most rapid and successful colonization events in human history. It proves that the Viking Westward Expansion was not just about raiding; it was about the sophisticated logistical movement of entire communities." — Dr. Soren Hauge, Professor of Medieval Scandinavian History.

Phase Two: Greenland – The Edge of the Known World

By the late 10th century, the best land in Iceland was taken. The same pressures that drove the Norse from Norway—overcrowding and feuds—began to bubble up again. The Westward Expansion needed a new frontier.

Enter Erik the Red.

Erik is the archetype of the Viking pioneer: violent, ambitious, and incredibly persuasive. Exiled from Iceland for murder (a pattern in his family), he sailed west into the unknown.

Phase Two: Greenland – The Edge of the Known World

The Greatest Real Estate Scam in History?

Erik found a massive landmass dominated by an ice sheet. But he also found deep fjords on the southwest coast that were sheltered and green.

When his exile ended, he returned to Iceland to recruit settlers. He knew that "Ice-land" was a terrible name for marketing. So, he called his new discovery Greenland.

He famously said, "People would be more inclined to go there if it had an attractive name."

It worked. In 985 AD, 25 ships followed him west. Only 14 made it. But those that did established the Eastern and Western Settlements. The Westward Expansion had now pushed the Norse culture into the North American tectonic plate.

Phase Three: Vinland – The First European Contact

The final, and perhaps most famous, chapter of the Viking Westward Expansion belongs to Erik’s son, Leif Erikson.

around 1000 AD, Leif bought a ship and sailed west from Greenland, following rumors of land sighted by a merchant blown off course. He wasn't raiding; he was exploring.

He found three lands:

- Helluland (Slab Land): Likely Baffin Island. Rocks and ice.

- Markland (Forest Land): Likely Labrador. Essential for timber, which Greenland lacked.

- Vinland (Wine/Pasture Land): Likely Newfoundland.

L'Anse aux Meadows

For centuries, "Vinland" was considered a myth. Then, in the 1960s, archaeologists discovered a Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Carbon dating confirmed it: Vikings were living in North America exactly 1,000 years ago. This site proves that the Westward Expansion had successfully crossed the entire Atlantic Ocean.

See more: Eric Bloodaxe: The Real Story of the Viking Brother Slayer

The Technology That Made It Possible

You cannot discuss the Westward Expansion without discussing the vehicle that made it possible.

The American pioneers had the Conestoga wagon. The Vikings had the Knarr.

While we often picture the long, slender warships (drakkar) used for raiding England, the Westward Expansion was fueled by the knarr.

- The Hull: Wider and deeper than a warship, designed for cargo (livestock, tools, families).

- The Power: Relied mostly on a large square sail rather than oars.

- The Capability: Could handle the rough, open swells of the North Atlantic better than any other European ship of the time.

Without the engineering genius of the knarr, the Westward Expansion would have ended in the bottom of the sea.

Comparative Analysis: Viking vs. American Expansion

To truly understand the magnitude of this achievement, it helps to compare the Viking Westward Expansion with the American Westward Expansion of the 19th century.

While separated by 800 years, the parallels—and the differences—are striking.

Tale of the Tape

| Feature | Viking Westward Expansion (c. 800-1000 AD) | American Westward Expansion (c. 1800-1890) |

| Primary Motivation | Land hunger, political freedom, timber. | Manifest Destiny, gold, land, resources. |

| Primary Vehicle | The Knarr (Ocean-going cargo ship). | Covered Wagon / Railroad. |

| Key Obstacle | The North Atlantic Ocean. | The Rocky Mountains / Deserts. |

| Indigenous Contact | Skrælings (Inuit/First Nations) - Hostile/Trade. | Native Americans - War/Displacement/Trade. |

| Government Support | None (Private enterprise/chieftains). | Heavy (US Army, Homestead Act). |

| Outcome | Temporary in America; Permanent in Iceland. | Permanent colonization of the continent. |

The Viking Westward Expansion was a decentralized, libertarian movement. There was no "Viking Army" protecting the settlers in Vinland. They were on their own.

Why Did the Expansion Stop?

If the Vikings were so successful at Westward Expansion, why aren't we all speaking Old Norse in New York today? Why did they abandon Vinland?

This is a favorite topic for historians, and the answer lies in a combination of economics and resistance.

The "Skræling" Resistance

The Vikings called the Indigenous people they met Skrælings. Unlike in Iceland (which was uninhabited), North America was fully populated.

The Vikings had iron weapons, but they were vastly outnumbered. The Indigenous peoples were skilled warriors who knew the terrain.

After a few bloody skirmishes, the Vikings realized that a permanent colony was impossible to defend with such a small population so far from home.

The Supply Chain Issue

The Westward Expansion had stretched the supply lines to the breaking point.

- Norway to Iceland: ~600 miles.

- Iceland to Greenland: ~750 miles.

- Greenland to Vinland: ~2,000 miles (coastal route).

To maintain a colony in Vinland, they needed support from Greenland. But Greenland itself was a fragile colony on the edge of survival. The Westward Expansion had simply gone one bridge too far.

The Legacy of the Viking Westward Expansion

The physical settlements in North America were abandoned, and the Greenland colony eventually faded away in the 15th century due to the cooling climate (The Little Ice Age).

But the legacy of the Westward Expansion remains.

- Genetic/Cultural Legacy: Iceland remains a vibrant, independent nation—a direct product of this expansion.

- Navigation Knowledge: The knowledge of lands to the west didn't entirely disappear. It lingered in the oral traditions of sailors in Bristol and perhaps influenced Columbus himself (who may have visited Iceland).

- The Spirit of Exploration: The Viking Westward Expansion proved that the Atlantic was not a barrier, but a highway.

A Counter-Argument: Was it really "Expansion"?

Some historians argue that "Expansion" implies a coordinated state effort, like the Roman Empire. They argue the Viking movement was more of a diaspora—a scattering of people fleeing trouble.

However, the organized nature of the Iceland settlement (landnám) and the planned colonization of Greenland suggests that this was indeed a structured, intentional Westward Expansion, orchestrated by brilliant leaders who knew exactly what they were doing.

Conclusion

The Viking Westward Expansion serves as a powerful reminder that the history of the Americas is far deeper and more complex than the narrative of 1492. Five centuries before the Santa Maria set sail, Norse men and women were forging iron and raising families in Newfoundland, their gritty reality of survival providing a tangible foundation for the legendary tales of valhalla. These pioneers pushed the map westward wave by wave, viewing the North Atlantic not as an empty void but as a highway of curiosity and a testament to the human refusal to accept the horizon as the end of the world.