When we picture the Vikings, we usually envision bearded raiders in longships, terrorizing the coasts of England and France. Yet, the story of the Norse people is far more complex than mere pillage. It includes one of the most astonishing and unique military formations in history: The Varangian Guard.

Imagine the fiercest, most disciplined warriors of Scandinavia—men who lived and died by the massive Dane Axe—not fighting against kings and emperors, but protecting the most powerful ruler in the known world, the Byzantine Emperor, deep within the glittering, impossibly rich city of Constantinople (Miklagard, "the Great City," as the Norse called it).

These Old Norse elite Viking warriors formed The Varangian Guard, the ultimate imperial bodyguard, whose loyalty was bought with gold and whose reputation was carved in blood. They were the emperor's ultimate insurance policy, feared by enemies and envied by rivals. Their very presence represented a spectacular fusion of the barbarian North and the sophisticated Roman East.

Our intent here is to offer an in-depth, 2,500-word look at this legendary unit, tracing their path from the frozen fjords of Scandinavia and the river roads of Rus' to the gilded corridors of the Great Palace. We will explore their origins, their unique battle style, their incredible pay, and the dramatic historical events where The Varangian Guard earned their formidable reputation.

The Road East: Origins of The Varangian Guard

To understand The Varangian Guard, we must first understand the Varangians themselves. This term, derived from the Old Norse Væringjar (meaning "sworn companions" or "men of the pledge"), was the Byzantine name for Norsemen, primarily Swedes, who traveled the great river systems of Eastern Europe.

The Trade Route to Riches

While the Western Vikings focused on raiding, the Eastern Norse, known as the Rus', established expansive trade networks running from the Baltic Sea down the Volga and Dnieper rivers to the Black Sea. Their ultimate destination was the crown jewel of civilization: Constantinople.

The Catalyst (988 AD): The definitive moment came when the Kievan Rus’ Grand Prince Vladimir the Great converted to Christianity and, in a diplomatic and military treaty with Emperor Basil II, sent 6,000 of his finest Old Norse elite Viking warriors to Constantinople as a gift and a pledge of peace. This influx of fresh, battle-hardened troops provided Basil II with the necessary loyalty and brute force to deal with internal threats. Thus, The Varangian Guard was officially formed as a permanent, mercenary unit.

The Road East: Origins of The Varangian Guard

Why Hire the Enemy? The Logic of the Byzantines

Emperors historically mistrusted their own nobility and local troops, who might have political allegiances. Hiring foreign soldiers offered an ingenious solution:

- Impartial Loyalty: As mercenaries, The Varangian Guard had no local political ties, no family loyalties within the Byzantine court, and no interest beyond their pay and the Emperor's safety. Their loyalty was pure, based on gold and contract.

- Unrivaled Ferocity: The Norse warriors brought a level of terrifying, berserk-like aggression that the disciplined, professional Byzantine soldiers respected, but rarely matched. They were shock troops designed to break the enemy line.

Anecdote: Imagine the Emperor facing a coup. His domestic forces might hesitate to strike down fellow Byzantines. The Varangian Guard, however, saw only contract breakers and enemies, offering ruthless, decisive action free from political conscience.

The Tools of Terror: The Distinctive Combat Style of the Guard

The defining feature of The Varangian Guard was not their numbers, but their weapons and their training. They were specialists in shock combat.

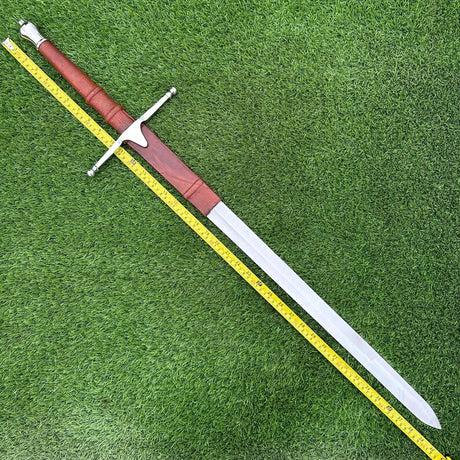

The Mighty Dane Axe (Breiðöx)

While the Byzantine military relied on balanced cavalry and precision archery, The Varangian Guard brought raw, terrifying force, centered on the use of the two-handed Dane Axe.

- Weapon of Legend: This massive, two-handed weapon could cleave a man—and his horse—in half. In the tight confines of a palace defense or the final push of a pitched battle, the sight and sound of a line of these Old Norse elite Viking warriors wielding their axes was a devastating psychological weapon.

- The Roar: Historical accounts mention their battle cry, a chilling mixture of Norse and early English, which struck fear into the hearts of their opponents—often described as sounding like thunder rolling across the battlefield.

The Pay and Plunder: Why the Varangians Came

These men were mercenaries in the truest sense, drawn by a promise of wealth far exceeding anything they could achieve in Scandinavia.

- High Salary: Members of The Varangian Guard received substantial wages paid in gold nomismata—the equivalent of a small fortune back home.

- The Polutron (Donation): The greatest draw was the traditional right to plunder the imperial treasury upon the death of an Emperor. While officially a "donation" (or Polutron), this tradition guaranteed that The Varangian Guard had a vested, financial interest in ensuring the Emperor’s peaceful reign but a lucrative, unconditional interest in his swift replacement upon death.

Statistical Look: Estimated Composition and Pay

While exact records are scarce, historians estimate the Guard's structure changed over the centuries.

| Period (Approx.) | Primary Origin (Norse/Viking) | Estimated Manpower | Annual Gold Pay (Relative to Common Soldier) | Role in Byzantine Army |

| Late 10th Century | Norway, Sweden (Rus') | 6,000 | 3-5x higher | Shock Infantry, Imperial Guard |

| Mid 11th Century | Vikings and Anglo-Saxons | 3,000–4,000 | 5-7x higher | Palace Security, Expeditionary Forces |

| Late 12th Century | Mixed Northern European | 1,000–2,000 | 7-10x higher | Ceremonial Guard, Last Line of Defense |

The consistently high relative pay demonstrates the supreme value the Byzantines placed on the absolute loyalty and combat effectiveness of The Varangian Guard.

The Golden City: The Varangian Guard in Constantinople

Their duties extended far beyond battlefield heroics. Within Constantinople, the Varangians were the ultimate power brokers, albeit ones who rarely engaged in political scheming themselves.

Palace and Prison

The Guard’s primary function was protecting the Emperor within the sprawling Great Palace. Their barracks were typically within the palace grounds, and they held keys to the prison cells where deposed emperors or dangerous conspirators were held.

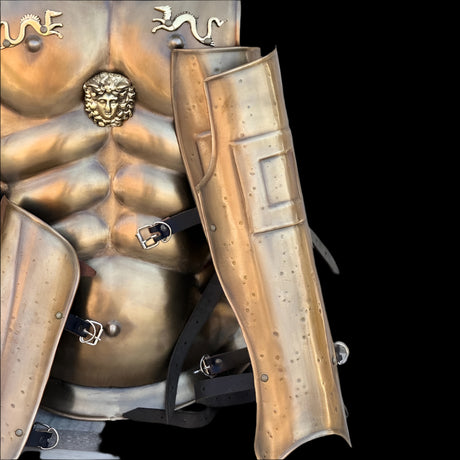

- The Intimidation Factor: The sight of a towering, mail-clad Norseman carrying a huge axe was enough to dissuade most courtiers from making a sudden grab for power. They were the visible embodiment of the Emperor’s absolute authority.

The Role of Famous Varangians

The history of The Varangian Guard is punctuated by the presence of historical figures who, upon returning home, became legends themselves.

The most famous member of The Varangian Guard was Harald Hardrada, later King of Norway (1046-1066).

Case Study: Harald Hardrada: Harald spent over a decade (c. 1030–1042) in the service of the Byzantine Empire. He didn't just stand guard; he fought on three continents—in Anatolia, Sicily, and Bulgaria. His saga describes him leading the Varangians on dazzling campaigns, culminating in vast riches and military acclaim. When he left Constantinople, he was one of the wealthiest men in Northern Europe, using his Byzantine gold and experience to successfully claim the Norwegian throne—a true testament to the financial opportunities afforded by serving in The Varangian Guard.

The Crucible of Battle: Campaigns That Defined The Varangian Guard

The Varangian Guard was frequently deployed as the Emperor’s trump card in crucial battles across the empire. Their fierce reputation allowed them to be used both as a spearhead for attack and an immovable shield in defense.

The Campaign in Italy and Sicily

Under Basil II, Varangians fought Arabs in southern Italy and Sicily. Their skill in close-quarters combat was essential in taking fortified towns. Historian John Haldon notes that the Varangians’ ability to withstand missile fire and deliver a decisive charge was "the Emperor's most reliable tactical asset."

The Crucible of Battle: Campaigns That Defined The Varangian Guard

The Battle of Manzikert (1071 AD)

This defeat against the Seljuk Turks is often cited as the beginning of the end for Byzantine power, yet the performance of The Varangian Guard remains notable.

- The Stand: When the bulk of the Byzantine army routed, the Varangians and other loyal foreign contingents fought a rear-guard action, famously attempting to rescue the Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes. Though they were ultimately defeated and decimated, they fought to the last man, demonstrating the fierce loyalty and warrior code characteristic of these Old Norse elite Viking warriors. Their sacrifice allowed many others to escape.

-

You may also want to check out this product: Storm Double Headed Axe

The Second Wave: Anglo-Saxons Join The Varangian Guard

Following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, a new, large wave of Northern European warriors joined The Varangian Guard, dramatically changing its cultural composition.

The Flight from Hastings

After the defeat at the Battle of Hastings, many disillusioned and landless Anglo-Saxon noblemen and soldiers chose exile over submission to William the Conqueror. They sought military service abroad, and the legend of the gold and glory of Constantinople drew them like a magnet.

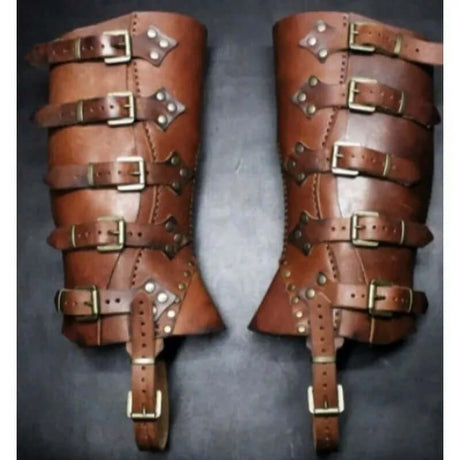

Cultural Shift: While initially and predominantly Norse, by the 12th century, The Varangian Guard had a strong Anglo-Saxon (often called Inglis) element. They retained the fierce tradition of the Dane Axe, reinforcing the unit’s specialized shock infantry role. This fusion created a truly pan-Northern European elite unit, united by shared warrior culture and opposition to the Normans.

Perspective: Dr. Judith Jesch, a leading scholar of the Viking Age, highlights that for these exiles, Constantinople was "not just a job opportunity, but a chance to live in a place of glory and dignity, away from the shame of defeat."

Nuance: The Language Barrier

The presence of Anglo-Saxons and Norsemen in The Varangian Guard meant the unit retained its "barbarian" identity, standing apart from the Greek-speaking Byzantines. Their languages were often unintelligible to the locals, creating a necessary distance that helped maintain their impartial, mercenary loyalty—a distance reinforced by their constant military activity.

- See more: Thor’s Hammer: Myth, Magic, and Mjolnir

The Twilight of the Guard: Decline and Legacy

The glorious history of The Varangian Guard finally dimmed with the gradual decline of the Byzantine Empire.

The Fourth Crusade (1204 AD)

The Crusaders' sack of Constantinople in 1204 was the ultimate tragedy for the Byzantines and the Varangians.

- The Final Stand: Contemporary accounts describe The Varangian Guard fighting valiantly until the very end, defending the walls and the palace against the Venetian and Frankish attackers. Their defense was ferocious, but ultimately overwhelmed by the treachery of the Crusaders.

- The Aftermath: Though the Byzantine Empire eventually reclaimed Constantinople, The Varangian Guard never recovered its pre-1204 strength or prestige. Later iterations of the Guard were smaller, poorer, and often recruited from other sources, diluting the fierce, specialized nature of the original Old Norse elite Viking warriors.

The Enduring Legacy

Despite their eventual dissolution, the impact of The Varangian Guard is undeniable. They left behind a rich tapestry of runic inscriptions (graffiti!) in places like Hagia Sophia, detailing their adventures and longings for home—physical proof of their service. They exported Byzantine gold, culture, and organizational ideas back to Scandinavia and England, forever linking the two worlds.

The Varangian Guard represents the ultimate transformation of the Viking spirit: from raider on the fringes of civilization to the ultimate defender of civilization's highest expression. They traded fleeting plunder for structured wealth, temporary glory for permanent legend, and chaos for the pinnacle of professional military excellence.

-

You may also want to check out this product: Kyivan Rus Knife

Conclusion: The Unsung Heroes of Byzantium

The Varangian Guard were elite mercenaries who traded raiding for the golden wages of Constantinople. As the Byzantine Emperor's shock troops, they represent a unique chapter in the tales of valhalla—one defined by adaptability and ambition.

In the halls of Miklagard, these warriors proved that Viking prowess could command respect and wealth far beyond the northern seas. They found their glory not just in myth, but in the service of an empire.

"Tales of Valhalla is an expert chronicler of the Viking Age, blending scholarly research with master storytelling to revive the Old North. From the hidden depths of Norse mythology to the tactical grit of the sagas, they provide authentic, rich insights into the warriors, leaders, and legends that forged history." - Specialist in Norse mythology and Viking history